everything can't be eugenics

you keep using that word, I don't think it means what you think it means.

I recently published a piece in The New York Times about being the parent of a child with profound autism, in response to Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s comments that children like mine “will never pay taxes, they'll never hold a job, they'll never play baseball.” While I am not a supporter of his, those comments do reflect my personal experience with parenting an autistic child.

Many people responded angrily, sharing that their autistic children were expert violinists, valedictorians, or world-class chess players. I wanted to reply, “Congratulations. You and your child are having a very different experience of autism than what he’s talking about!”

It is a terrible thing to have to describe your child in terms of their deficits, but under our current systems, it’s often the only way to access adequate support—and the only way people will take seriously just how much these families need. The reception to the piece was overwhelmingly positive, but I still waited with bated breath for the inevitable unkind comments. Here are a few that accused me of promoting “eugenics” simply for speaking honestly about my child’s struggles:

Eugenics, the practice of attempting to improve the genetic quality of a population, was once popular in both Europe and the United States. That changed, of course, when Hitler used it to justify breeding an Aryan race, and more people came to recognize that government-forced sterilization is, to put it mildly, a horrifying idea.

But prior to World War II, the United States was also forcibly sterilizing disabled people. This isn’t a practice any mainstream American would defend today, yet there remains an uncomfortable gray area when it comes to discussing disabilities that severely limit a person’s quality of life.

Most of us would agree, without hesitation, that the government deciding who gets to reproduce based on a set of so-called “desirable” traits is terrifying and fascist. But when parents make deeply personal choices about reproduction in the face of significant disability—does that make them eugenicists too?

Recently, a couple on TikTok with osteogenesis imperfecta, also known as brittle bone disease, came under fire for choosing to have a baby. Their child, who was born with the same condition, has been in the NICU for six months. Critics called the couple selfish and short-sighted. Others defended them, arguing that the ability to have children shouldn’t be reserved only for non-disabled people.

My favorite comment was: “Saying they shouldn’t have a baby is implying that people with their condition shouldn’t exist.” Some videos with 100k+ likes went so far as to claim that simply questioning the ethics of their decision was an act of eugenics.

One piece of context that often seemed to get lost in the discussion is that the parents in question require full-time caregiving themselves, and it’s still unclear how they would be able to care for a child. That introduces several layers to the conversation: Can disabled parents who know they may pass on a serious condition ethically decide that, while life with a disability is difficult, they are still grateful to be alive and are comfortable with the possibility of passing that condition on? And separately: Should people—disabled or not—who are unable to care for a child on their own have children? The first question feels very nuanced, although I would argue that choosing to live a full and happy life even though you were dealt cards that inherently make your life more challenging is different than intentionally passing those challenges on to a child. The degree to which you feel like your own quality of life has been compromised is deeply personal, which is why you see folks who are depressed or have ADHD say its why they won’t have children, even though there are folks all around us with those conditions raising children. As for the second question: personally, I believe that if someone—regardless of ability—is not able to care for a child, they probably shouldn’t have one. But when I’ve said this publicly, it has sparked strong reactions. On platforms like TikTok, commenters have argued: “Everyone needs support in parenting; none of us can do it alone,” or, when someone voiced concern about bringing a child into the world to suffer, others shot back: “We’re all suffering. If you were ideologically consistent, you’d be an anti-natalist.”

It reminded me so much of the comments I’ve received about my daughter, who is seven years old and nonspeaking, comments that often feel like a form of emotional gaslighting. I’ve had people ask if I’m even sure she wants to talk, suggesting that maybe she prefers to be nonverbal. Others have said things like, “If you didn’t want a disabled child, you shouldn’t have had a child at all.” Why? Because holding multiple truths makes people uncomfortable. You love your children and that’s why the disability is hard—because it’s hard on them! It’s like telling someone your child has a life-limiting condition and them replying, “all of our lives have limits!” It starts to sound like the “all lives matter” of the disability movement, the outright denial that there are folks who experience disability in a much less palatable way.

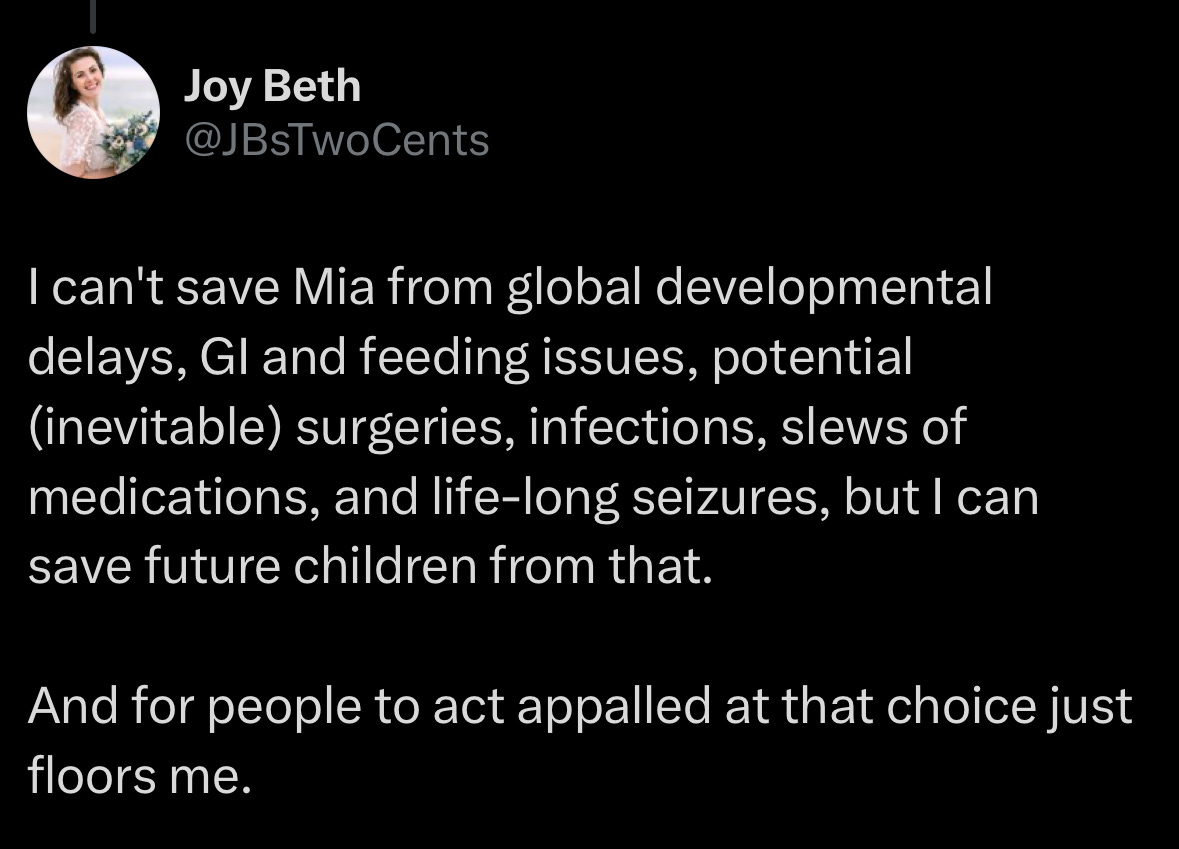

When your child’s disability severely impacts their quality of life, the natural instinct is not to reject them, but to wish they didn’t have to suffer. I want the world to be more inclusive for her—but no amount of inclusion will fix some of the things she wrestles with. A dear friend of mine, whose daughter has lissencephaly—a rare, life-limiting neurological condition in which the brain lacks the folds that allow for typical development—spoke bravely about why she and her husband are choosing IVF to have another baby:

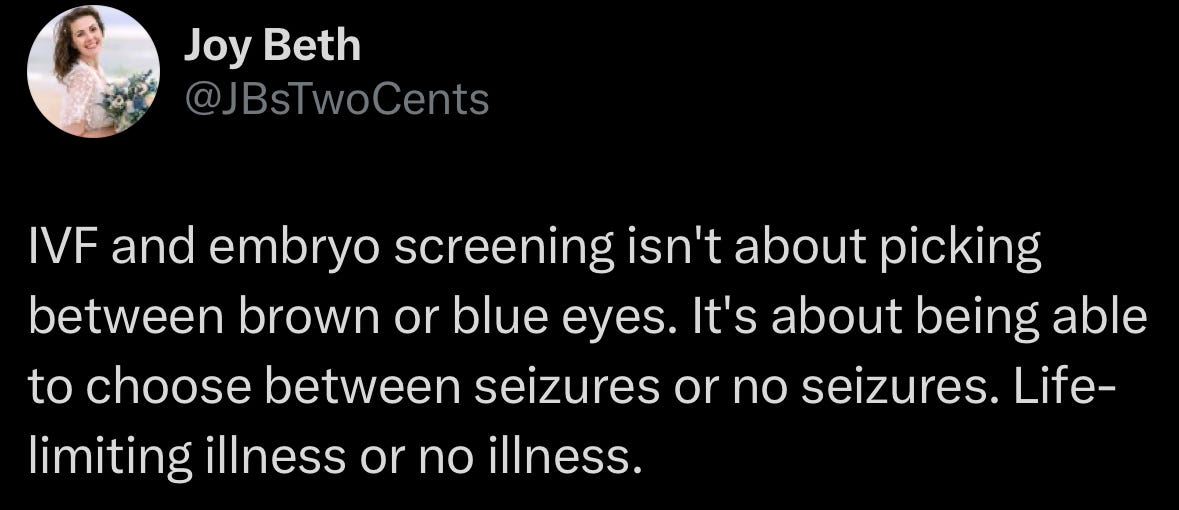

I especially appreciated her comment that IVF is not parents choosing between brown and blue eyes, but parents making difficult decisions that come from the devastation of knowing the suffering certain disabilities can bring. While there is a small subset of people who want "designer babies" , wanting your child to be less disabled isn’t treating your child like an accessory. It’s not about aesthetics or perfection. It’s about the reality that parenting a profoundly disabled child is a different and often overwhelming experience—especially when your child may never reach the milestone of independence. For those of us who have experienced “typical” parenthood alongside disability parenting, there are parts of it that are almost incomparable. Especially for folks with medically complex children, many of whom have in-home nursing care, or the parents have to become proficient in skills to keep their child alive that the average parent never considers.

The problem with using the term eugenics to describe both the systematic murder of disabled children in Nazi Germany and parents who use embryo selection to avoid fatal conditions is that it draws a false moral equivalence between genocide and grieving parents trying to prevent future suffering. It flattens complex ethical terrain, shuts down nuance, and dismisses the lived realities of families making deeply personal, often heartbreaking choices. It also dehumanizes those parents by casting them as ideologues rather than individuals wrestling with love, loss, and fear.

So we’re left with a question: is eugenics a moral spectrum, with some actions more ethically defensible than others, or do we need an entirely different vocabulary to describe these vastly different intentions and outcomes?

What’s clear to me is that these issues aren’t black and white, and tribalism that ignores realities on both sides of this argument will ultimately undermine advocacy and the disability community as a whole. My daughter deserves to exist and have the best life I am able to give her. I wish life was easier for her. These two things are not in opposition.

This is a well thought out piece inspiring careful thought on the subject of eugenics. Thanks for this Emily.

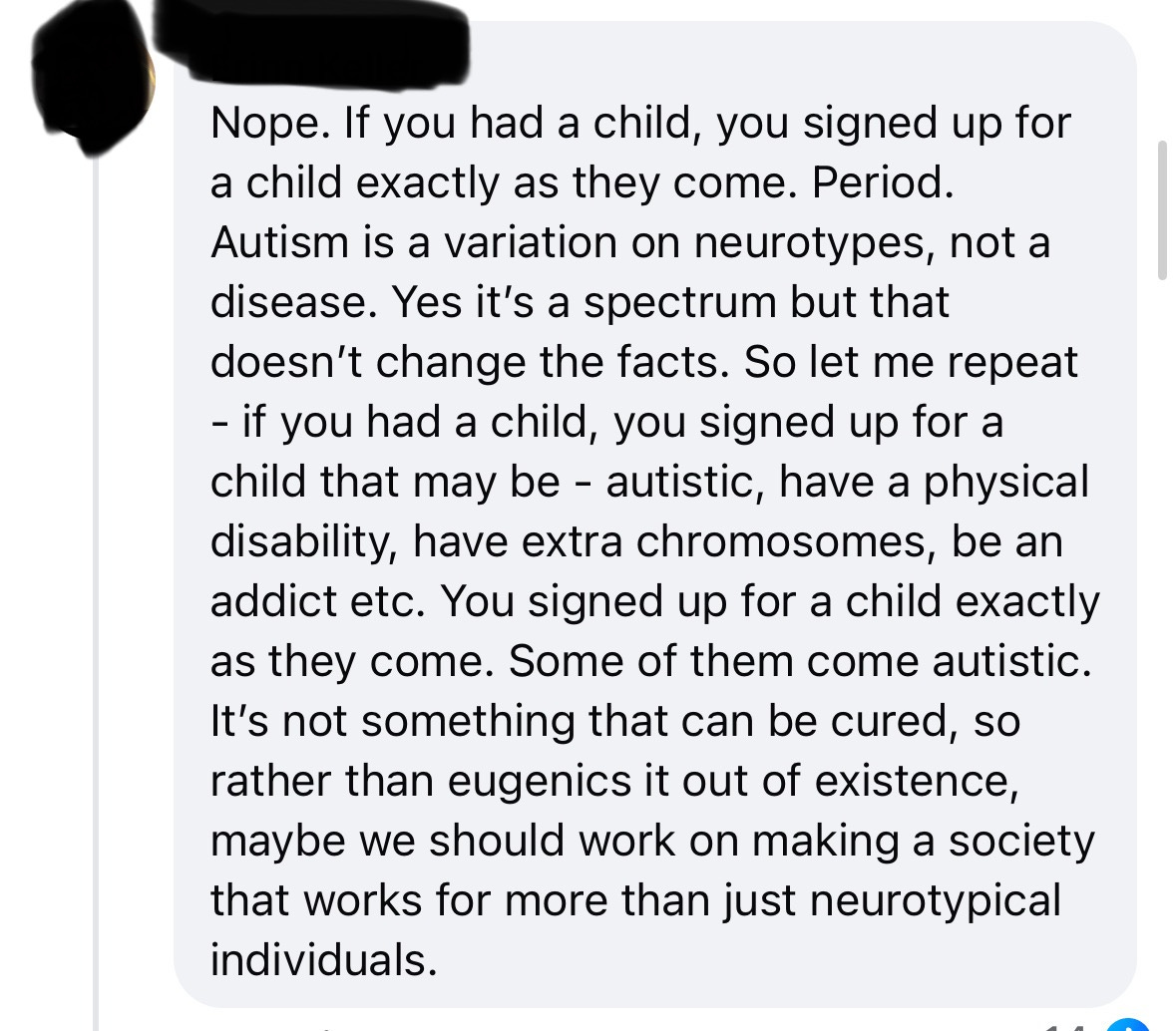

I’ll make this very simple for you: If you want to become a parent, you have at least two jobs to do. Your first job is to accept your child exactly as they are. Even if a school or an employer cannot accept and/or monetize them. Fuck “independence”. And, your second job is to relieve your child’s suffering, EVEN IF YOU CONTINUE TO SUFFER. Perhaps you would “suffer” less, if you killed your “defective” child. You strongly support the “horrifying” concept of a “master race” and murder is the best way to build one. But, that doesn’t matter. IT IS EVIL TO CANCEL A PERSON’S LIFE BECAUSE YOU WILL NOT VALUE IT.

I hope that helps. 🙂